Janice Arnold interview: The origins of Felt

Janice Arnold spends her time passionately pursuing a deeper understanding of Felt. Having spend a significant amount of time in Asia learning Felt from a high tech and industrial perspective, her current work projects an aura of sensibility.

Although a successful independent artist, Janice enjoys the opportunity to collaborate with others.

Additionally, she has a packed calendar, with numerous workshops to run and exhibits to attend.

In this interview, Janice Arnold reveals her discovery of the origins of Felt, what it means to be pushed beyond her comfort zone, and the need for balance in her work.

A quality that escapes conscious detection

TextileArtist.org: What initially captured your imagination about textile art?

Janice Arnold: Textiles have been integral to our existence for millennia and offer a link to our sometimes forgotten collective past. I’ve always been captivated by fine fabrics, and have studied many textile traditions. When I first witnessed felt making, it seemed a strange form of magic. Featherweight tufts of raw wool combined with hard work created a dense, strong-textured material with a natural edge that was unlike anything I had ever seen! I’ve come to refer to this transformation as ‘Fiber Alchemy’. There is no tool between the hand and the raw fiber. Once I learned the origins and rich history of Felt, understood the process, and realized the tremendous variety of raw fibers available, I didn’t look back.

Our modern life, driven by a predominance of synthetics and technology, is far removed from nature and our historic traditions of making things by hand. We may be smarter in some ways and more advanced, yet decidedly starved for organic textures and irregular forms. It is from this perspective that handmade textiles offer characteristics and qualities that are missing in machine-made materials. Not only are they visibly different, healthier to be around, and more comfortable, I believe they transmit my energy and the Felt, in turn, exudes a quality that escapes conscious detection. In this way they can heal—in a beautiful way—some of the inhumanity in our modern environments.

You talk about discovering the origins of Felt. Can you explain what you mean by that?

Felt is believed by many scholars to be our ‘first textile’. In Central Asia, sometimes called the birthplace of Felt, the survival and advancement of nomadic cultures depended on this miraculous material made from raw wool.

I call it miraculous because wool breathes, insulates, absorbs and releases moisture and has been serving those functions for thousands of years. These features are the result of millions of years of evolution that allow sheep to endure extreme climate changes.

My research, travel and experiences with nomads in Central Asia and Mongolia have informed my opinions, shaped my process and given me a profound appreciation for this tradition. I witnessed this ‘first textile’ as it has been made for thousands of years, and realized it was also a community based fabric—sometimes requiring a village to make the Felt required for a large yurt. A massive model for the social principle of cooperation and teamwork, this concept is what drives my frequent inclusion of community involvement in my large scale Felt pieces.

Living in harmony

Can you talk more about this traditional process and how it informs your work?

It is simply incredible that for thousands of years humans have been making Felt and the basic principles have not changed. Raw wool—in it’s purest state—grows as individual hairs on a sheep. When removed from the animal, these hairs form wispy and cloud-like tufts. Because of wool fiber’s unique physical and chemical structure, when it is manipulated with friction, moisture and pressure, the fibers will intertwine and matt. The more it is manipulated the more it shrinks and the denser and stronger it becomes until the fibers are irrevocably locked together.

I have learned to collaborate with these naturally occurring phenomena and use them in new combinations and forms with other raw materials as a form of expression. This intimate understanding of process, guides the my work and my visions, all the while honoring the past and offering hope for a future.

Wool has infinite potential as a core raw material. As modern society shifts more towards seeing the value of living in harmony with the environment, a wisdom that nomadic cultures epitomize, Felt has been rediscovered. The renaissance of this ancient material is remarkable, and the diversity and discoveries emerging along the continuum from utility to fine art appears limitless.

What or who were your early influences and how has your life/upbringing influenced your work?

My childhood played a big part in the way how I evolved as an artist and a person. In my family the line between work and passion was very blurry. My father was a civil engineer by day and cartographer by night. My mother’s passion was quintessential for the era—supporting my father’s endeavors and raising the children. She was at heart a maker who embodied an inventive, creative, selfless spirit and lived life in a profoundly positive way—regardless what challenges she faced.

I was the youngest of four children, and as soon as I could walk I became the youngest member of the Arnold Family Survey Crew. Every weekend we took family ‘field trips’ to measure new roads for my father’s maps. My job as a toddler, was to hold the end of the surveyors tape in the slow and deliberate process of the surveyors documentation. I must have learned focus and patience at this point. Back home I would sit with my father at his drawing table. I watched him translate, with intense precision, the coordinates with a slide rule, and reduce our day’s work into thin inked lines and dots on his waxed linen master maps. I recognize now that this process was the basis for my innate sense of scale and an uncommon perspective of the world and materials around me. My life long involvement with maps, geography, science, nature and travel shaped my perceptions and imagination—it gave me a global perspective and has benefited me in every aspect of my life. It took a long time for me to realize that not everyone saw textiles covering landscapes or fields of texture and color.

Ancient traditions and techniques

What was your route to becoming an artist?

I have always loved making things. Undoubtedly, this stems from my frugal upbringing- where nothing went to waste. I learned to sew by altering the clothes passed down from siblings. I don’t remember having toys, just tools and raw materials. If I didn’t have the right tool, I figured out how to fashion one. This environment helped develop my design sense and critical thinking skills.

As a teen and young woman, I read incessantly. I was fascinated by fashion as an expression, folk art traditions, costumes and textiles. I received my BA at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, WA, while also being self-employed in a number of artistic entrepreneurial ventures.

When did you start making Felt?

My first handmade Felt project was in 1999. It involved making about 200 sculptures for a high end fashion retailer as part of their fall store windows. I conceived and designed them to be 8 foot tall exaggerated forms of clothing, with seams exposed and natural edges in contrasting colors that embodied the colors of Fall Fashion that year. These sculptures appeared in store windows in over 30 cities across the US. It was in a sense my series of ‘Multiples’, a term coined by Joseph Beuys.

To accomplish this, I had to learn how to make Felt! At this time, making handmade felt was obscure. A friend coached me in felting basics. After some humorous and painful learning experiences, I discovered the best guide for creating this quantity and quality of Felt was actually history. Through study and research, I discovered the ancient traditions and techniques of Central Asian nomads, who have been laying up raw sheep’s wool and then rolling it over the tundra behind a camel or a horse for thousands of years to make the covers for their dwellings.

After making 1500 square yards of handmade Felt for this project, I gained an intimate understanding of the material and process. The finished pieces were over eight feet tall, sculpted, stitched and placed on tall custom forms I created for each piece. The installations were a huge success. I’m quite sure I am the only person on the North American continent who has made handmade Felt on this scale. This attracted attention and some interesting projects, and through those projects I have evolved as an artist.

Industrial Felt emerged

What are your techniques?

First and foremost I honor the ancient traditional ways. Laying up raw wool is like a form of personal meditation and an opportunity to pay homage to sheep for their gift of wool.

By making gratitude one of my basic practices in making Felt, I can be open to any mistakes as guides in the process.

Because I was not formally taught to make Felt, I developed my techniques studying nomadic ways, using trial and error, common sense, experimentation and a refined sense of quality.

I see myself as an inventor and explorer, developing unique variations and processes for each new combination of fiber that I create. I use a variety of tools, and have developed hundreds of techniques over the years—some unique to the specific Felt I am making.

This naturally leads me to the fact that there is a lot of confusion about Felt as a material and a process. I will reserve my thoughts and opinions about the details of this for another discussion.

But for the question about my techniques, one needs to understand that I recognize only one technique for making what I consider ‘true Felt’.

‘True Felt’ by my definition is Felt made in the traditional way—a process requiring moisture, agitation and pressure. In my opinion this ancient process and resulting material is at the single root of what has now become a diverse group of materials, techniques, functional objects and forms of artistic expression.

I also work with industrial Felt and industrial processes, including needle-punching machines and carding machines. These originally were part of the industrial revolution and through these mechanical inventions, industrial Felt emerged.

As exploration of all types of Felt expands, so do new techniques, tools, fibers, machines and treatments. With these new approaches, the variations continue to expand. It’s a perfect example of Marshall McLuhan’s notion that first we build the tools, but then they build us. The needle used in needle-felting was first designed during the invention of the industrial needle-punch machine. That single individual needle, removed from the needle bed, opened the door to what is a whole culture of artists sculpting small objects out of raw wool.

There is now also US made cottage industry needle-punch machine. This puts the power of the large industrial machine into the hands of the artist and designer, offering opportunities limited only by the imagination.

I continually explore, incorporate and invent new techniques and explore new tools; however, a few principles stay constant:

- Not all Felt is created equal.

- Not every technique or quality of Felt will not be appropriate for every application.

- Not every technique will be compatible with every fiber.

- Each type of fiber has unique characteristics that influence the final product.

- Refinement is a long process.

- Quality & excellence above all else must be a constant.

Sometimes in my art practice the end use drives the technique; other times, the material drives the end use.

The notions of Felt

How would you describe your work and where do you think it fits within the sphere of contemporary art?

I see myself as a visual artist who has been drawn to the natural qualities of raw natural fibers. By collaborating with the naturally occurring properties of these materials, I’ve discovered a new dimension of expression in my art practice. I create visual tactile experiences as well as things of beauty and purpose using materials that offer a sensory response.

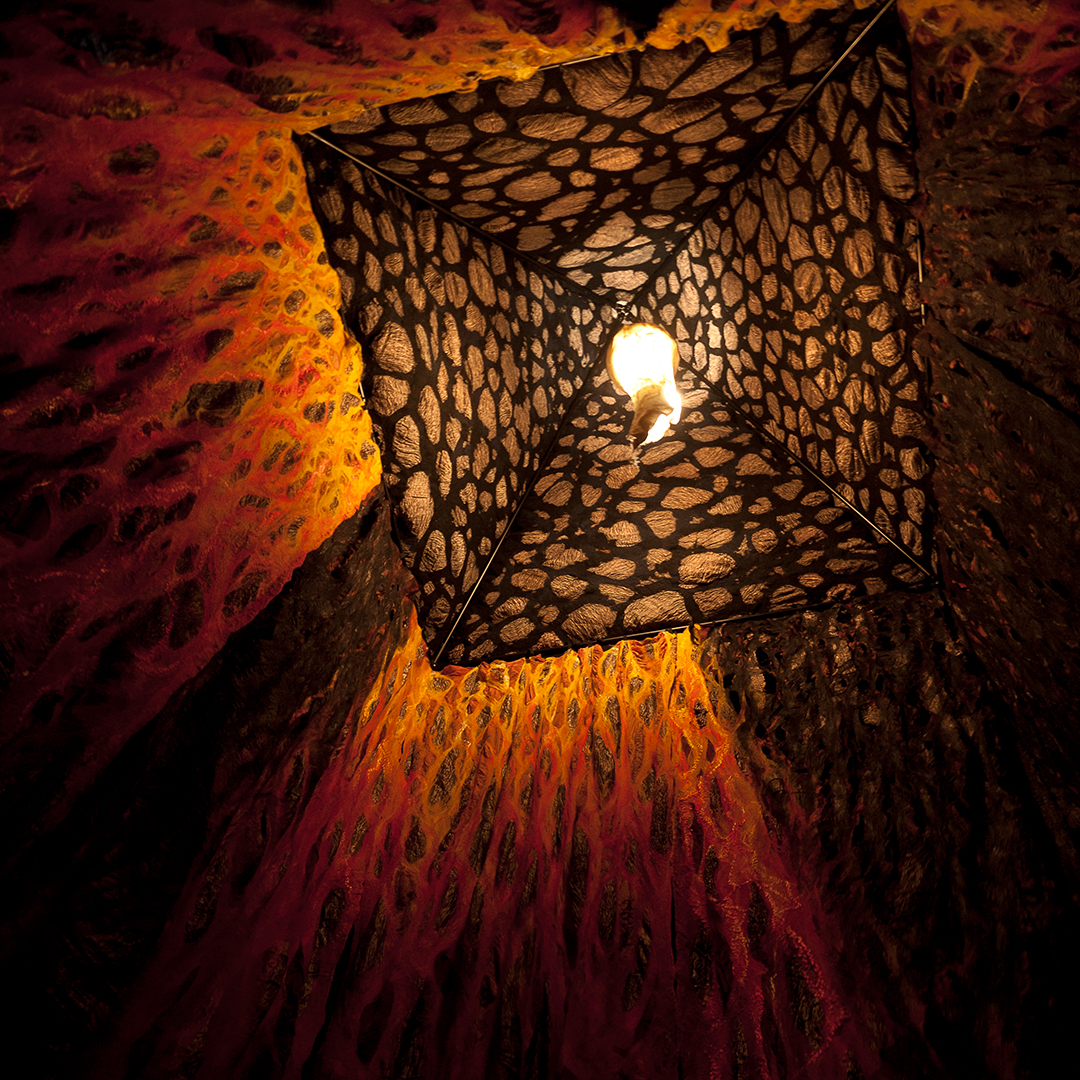

I love to play with space and perception and push the boundaries on what people expect in contemporary art… to create environments and experiences that allow us to feel differently (hopefully better!) to experience spaces differently, to consider materials differently.

Some call me an extreme felter. I think this is in response to my drive to break boundaries and limits that exist in the preconceived notions of Felt. I also push myself beyond my comfort zone as an inventor and explorer. I seek the uncharted territory. Felt has been my vehicle on that journey. Wool is always an integral part of my installations, and every square inch is made with intention.

I believe Felt has many important qualities that could be of benefit in our built environments. It is an art form and material that serves multiple purposes. An example of this cross-collaborative design approach is demonstrated in my bespoke Felt wall treatments. These are aesthetically beautiful, sound absorbing, insulating, non-toxic and environmentally sustainable and USA made, all which add up to being cost effective.

Tell us a bit about your process and what environment you like to work in.

I work out of a decommissioned schoolhouse built in 1922. It sits on two acres in the middle of a prairie covered with native grasses and Camus. Without this luxurious amount of space, I wouldn’t be able to work on the scale I do.

Making huge pieces of Felt is extremely wet and sloppy work. Much of the wet work occurs outside – regardless of the rain, snow, ice, mud or sun. This keeps me in touch with nature and the Central Asian nomadic community.

Do you use a sketchbook?

Absolutely! As well as graph pads.

An idea or vision

What currently inspires you and which other artists do you admire and why?

I find inspiration everywhere, and I take an ontological approach to design, meaning inspiration is the byproduct of my mindset, which embodies an infinite sense of innocence and wonder.

Specific things that inspire me to create a new piece of work can be almost anything—a challenge, a space, a fiery volcano, tree bark, an aerial view, or an insect. Sometimes it is a feeling or a pattern created by light or shadow, a stone, lines on a map, the color and form of a leaf, a piece of lichen, landscapes, textures, even a piece of cement can spark an idea or vision.

I love to combine opposites and play with contrasts. The juxtapositions of hard with soft, new with old, yin with yang.

Artists I admire:

- Lenore Tawney

- Magdalena Abakanowicz

- Christo & Jean Claude – scale and vision

- Andy Goldsworthy – collaborations with nature

- Janet Echelman – thinking outside the box and not being afraid to take leaps of faith and see the world in new ways

- Kurt Perschke – The Red Ball Project

- The Unknown Craftsman

- Mia Lynn

- Patrick Dougherty

- James Turrell

- Sheila Hicks

- Ann Hamilton

- Bernhardt Edmaier

- Ellsworth Kelly

- Jack Lenor Larsen

What advice would you give to an aspiring textile artist?

Beginners of any textile art should study quality first then seek refinement. They should focus first on learning the inherent properties, quality and beauty of their craft before imposing design into it. Every artist—new or not—needs to learn to step back and look at their work from a distance and with a critical eye. Consider how it could be improved and seek perfection.

Remember the most important part of the creative process is focus. By being fully present in my art practice I have discovered a lot about the material and myself. I see many young people who are impatient and want immediate results or answers. By contrast I listen my intuition and the voice of the material as it evolves. I become one with the process and do not rush it.

For feltmakers specifically:

The feltmaking process seems deceptively simple in the beginning. However if one only learns to make an item, like scarf or a hat, it is easy to miss important principles that rule the larger picture of the material. I recommend learning the traditional process—the nomadic way first. Then move into applying those principles to more avant guard approaches. I’ve started teaching a class I call ‘Felt like a Nomad’. This was a direct result of seeing too much Felt that had not been properly fulled (shrunk) and made without any knowledge of the origins or basic principles of Felt. I consider this poorly fulled wool to be unfinished and incomplete. Unfortunately it will not hold up to use, and reflect badly on the material in general. Learn to push yourself and the material to achieve excellence.

Learn – explore – make mistakes – remain open-minded and listen to the voice of the material.

Think critically

Can you recommend 3 or 4 books for textile artists?

- Art and Textiles – Exhibition Catalog, KunstMuseum Wolfsburg 2013

- Mindset – Carol Dweck

- Textiles: The Whole Story – Beverly Gordon

What other resources do you use?

The computer is a great tool, but frankly I use it judiciously. It is easy to think all the answers can be found online. It seems to me there are as many right answers as there are wrong answers. Over time, dependance on the internet may affect the evolution of common sense as well as ones ability to think critically and be creative.

What piece of equipment or tool could you not live without?

Pencil, eraser, graph paper, vellum, scissors, and a fountain pen.

Do you give talks or run workshops or classes? If so, where can readers find information about these?

I will be giving lectures and presentations on a variety of topics, as well as attending community feltmaking events. More details can be found on my website and Facebook page.

Additionally, I will be running two different workshops:

- Traditional & Contemporary Felt

- Professional Development

Where can readers see your work this year?

- Lecture/Presentation – May 2015, FeltRosa Conference, Italy

- Installation, Presentation – June 2015 Fiber Arts Festival, Lake Oswego, OR, USA

- Exhibition & Workshops – Fall 2015 Dyeing House Gallery, Prato. Italy

- Exhibition, Installation Aug 2016 – Jan 2017. San Francisco Museum of Craft & Design USA

Want more info? Please visit: jafelt.com

Janice Arnold has a busy year ahead! If you could ask Janice any question about her work, what would it be? Leave a comment.

Hello my name is Jason , and I was scrolling through the internet and i came across this article about an artist Janice Arnold , it raised an eyebrow for me because on my wall in a frame is an what looks like an water painting signed by a Janice Arnold …I would like to share pics to confirm or not it is the same person ,,that would be helpful i tried to search myself but hit a wall..

Thank you for your time

Hi Jason,

I would advise getting in touch with Janice directly, http://jafelt.com/

All the best,

Charlotte from the textileartist.org team