Ruth Miller: Life-sized storytelling in stitch

Ruth Miller cares as much about the narratives of her work as she does the actual images themselves. She’s committed to telling stories about the joys and challenges of daily life, especially for those living in African-American communities.

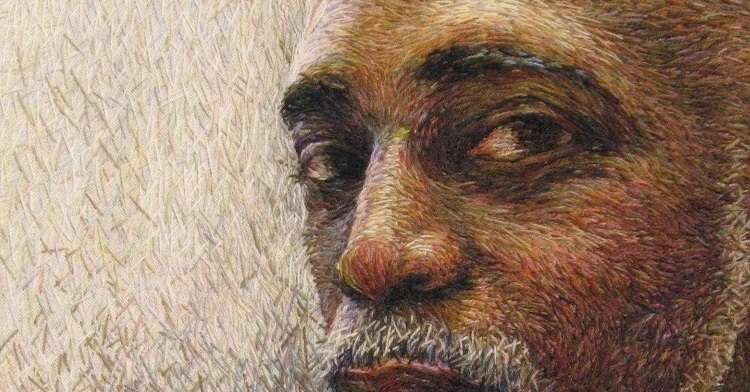

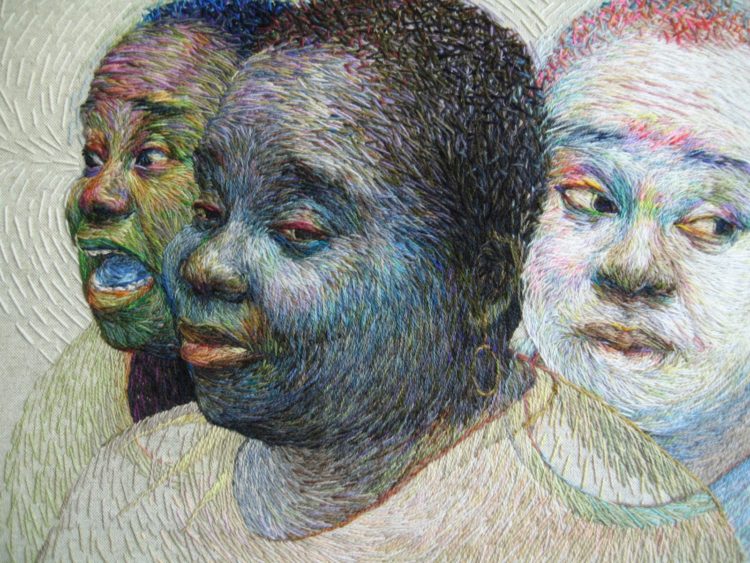

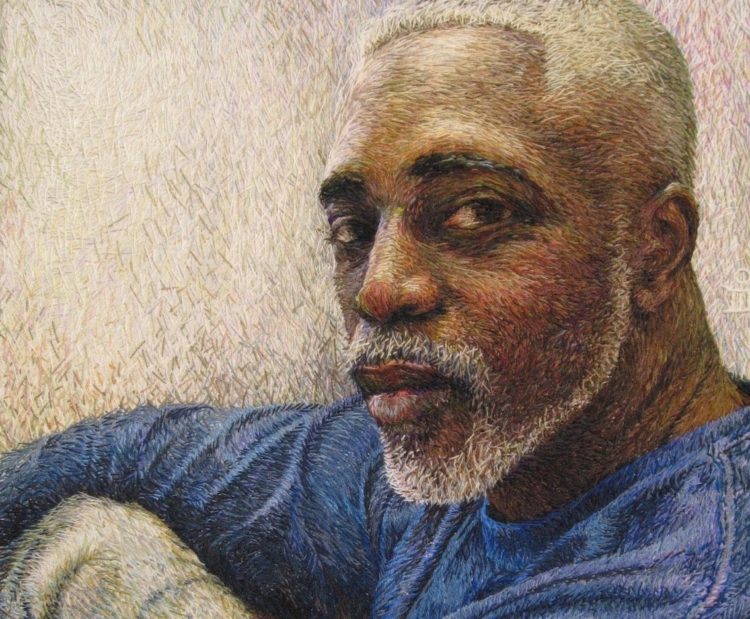

To say her pieces are remarkable is an understatement. Not only are her works life-sized, but they’re also entirely handstitched with tapestry yarns. Her ability to blend and merge fibre is unmatched. Upon close inspection, the viewer is amazed at the intricacy of layer upon layer of colour and stitch. The fact a single piece can take at least a year to create becomes readily apparent when viewed up close.

Ruth’s unabashed sharing of her artistic journey is a must-read. You’ll learn as much about the influence of politics and race on her work as you will her stitching techniques and colour theory. We’re so grateful for her honesty and encouragement to our readers.

We also invite you to view her work and process in this short video:

Ruth has received several awards and recognitions for her work, including the 2019 Mississippi Governor’s Award For Excellence in Visual Art. She also teaches across the US, including the Penland School of Crafts and the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art.

Her tapestries have been exhibited at the Mississippi Museum of Art, the Huntsville (AL) Museum of Art and in a solo show at the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art.

Finding an artist’s way

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium? How was your imagination captured?

Ruth Miller: What initially attracted me to textiles as an art medium was the fact the materials were clean and dry. Paint, by contrast, was wet, slippery and oily in consistency and required toxic liquids to clean up.

What or who were your early influences and how has your life/upbringing influenced your work?

My earliest work was created when I was a child. If no one else counts that but me, it’s OK. I was a latchkey kid, and drawing was a way to create the companionship I didn’t have. It was very personal and satisfying.

Early on, pencil drawing was my primary mode of expression. At both The High School of Music and Art and Cooper Union (New York City schools), I was taught to draw with succinct lines that had no shading. Perhaps this pre-disposed me to value line as a descriptive element.

In addition to encouraging me to apply to those fine schools, my mother also made sure I had a well-rounded cultural education that included dance, theater, and music. She also sent me and my siblings to the best public schools and to summer camp in Maine where I learned to love and care for the earth.

When I encountered Japanese woodblock prints, I was very impressed by their masterful uses of line and pattern set off by flat areas of color. I loved to browse in Manhattan bookstores, and I’m guessing that’s where I encountered the prints since most art history books tended to be Eurocentric. The flat areas of color bordered by lively use of line were things I strove to emulate.

My piece ‘Eshu’ featured on my website demonstrates that style, and later on, one can see remnants of it in my self-portrait called ‘Flower.’ But at that point, I found the style was insufficient in that I wanted to give viewers more ‘information’ about the subject, hence the shading.

All these things have given me context for the experiences of my life from which I draw the stories in my art. The love that drove my mother to be so tireless in her support allowed me to seriously consider the idea I could pursue this career that, on the surface, seemed to guarantee poverty. I could become an artist simply because it would make me happy.

Picasso might have been rich in those days, but few other artists seemed to be. Imagine that kind of freedom!

What was your route to becoming an artist?

The route of my career as an artist was full of twists and turns. Attending Cooper Union was a head-start. but I left before I got a degree, unaware that teenage insecurities were almost universally common and would dissipate with time. I was the only ‘openly’ black student at the time. There were other black students, but their skin tones and cultural knowledge helped them ‘pass’ for white. While all of my peers were very friendly, I still felt isolated and often cut class to visit Harlem where I knew no one, but I blended in.

(For more information on ‘racial passing,’ Ruth suggests reading journalist Joe Mozingo’s autobiography The Fiddler on Pantico Run: An African Warrior, His White Descents, A Search for Family .)

It also didn’t help that the classes I was most interested in were the first-year basic courses. So, I figured I could learn by just making art by myself. Eventually, I felt the school was a waste of my mother’s money, so I dropped out.

I later ended up getting a BA degree from The City College of New York which was my mother’s alma mater. I didn’t think I needed that either, but a wise friend prevailed by insisting I complete it just in case.

I had confidence in my artistic skills, but still no personal confidence. Shyness was a handicap. And I assumed (probably correctly) my teenaged self would not be accepted as a professional in the world of art galleries. This was back in the mid-1960s before I had heard about black women artists like Judy Chicago, the ‘Guerilla/Gorilla Girls’, and Faith Ringgold who protested against lack of inclusion in main art circles.

Furthermore, I had no ‘narrative vision.’ I was unacquainted with that concept which suggests instead of merely presenting various objects or subjects in a piece of art, there is also a story an artist is trying to tell–a point (s)he is trying to make. That point is what I call a narrative or story.

As a young adult working at whatever job would pay me, art creation was something I squeezed into my routine because I couldn’t imagine living without it. For a while, making accessories for myself and friends was as creative as I could get. I first made beaded earrings with mostly glass seed-beads strung on copper wire. Later I crocheted caps and drawstring bags out of heavy cotton threads.

But all times, including now, I sewed my own clothing. Not all, but at least somewhere between 50 and 80 percent of my wardrobe.

With age came personal confidence. Ten years ago, I moved to a rural area with low living expenses and the healing presence of a tree-filled yard. I imagined I would work intensely on a collection for a solo show going pretty much unnoticed.

I was surprised I not only attracted attention but also lots of support. In fact, generally speaking, there are loads of artist opportunities out there. Seeming scarcity is merely due to the fact an individual artist often doesn’t have pieces of the type requested in artist calls (subject, size, whatever). But, if she keeps working, she will eventually have just the right piece at the right time.

At least a year in the making

Tell us about your process from conception to creation

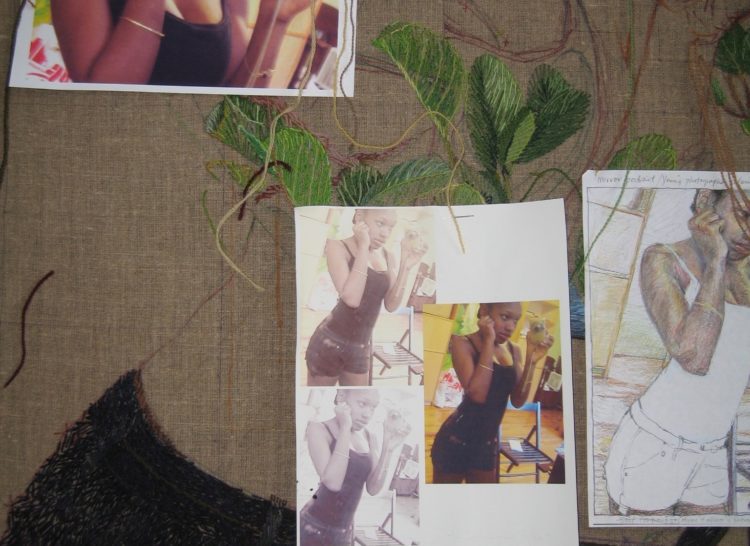

My process for creating portraits now often begins with narrative. Either the art-gods provide inspiration or I take a photograph that unexpectedly hints at a narrative. Interacting with models and just continuously shooting will often give me images I hadn’t thought about before. I will ask a model for a certain pose or give them a thought or situation to imagine and then start shooting before and after they have posed. This often gives a more natural stance to the person, because they are less self-conscious.

Each photo is the basis for a simple line drawing that is photocopied, and then I experiment with color and shading using colored pencils. Grids are then used to transfer the drawings to the stretched fabric. Lastly, the stitching begins.

All the photos, drawings and color reference materials are referred to throughout the entire process. I use only the simplest of stitches, letting the medium of embroidery take second place to the story I wish to tell.

My pieces may take a year or more to complete because every line or area of color is composed of several small stitches. There are no sweeping lines or sections that might take one or two seconds like a paintbrush in a painter’s hand. Instead, the needle goes in and out, and I have to first decide where it will go in and out. This requires thought.

Now multiply all that time for thought by the area I have to cover in a life-sized or larger portrait, and you can see why my pieces take so long to create. I seldom get weary of the process, but sometimes a deadline looms. And sometimes I run out of ideas and have to wait.

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques and how you use them

So far, I haven’t explored the far reaches of embroidery’s capabilities, let alone added other media to it. My stitches are pretty much just substitutes for brush strokes. Right now, needle-in and needle-out is all there is. Straight lines hint at form through directional placement and color contrast.

For example, in order to make the edges of an eye curve, I must use several small straight stitches to describe the curve. There is no such thing as a curved stitch. Every stitch is straight and may only look curved because the viewer can’t see where one stitch ends and the next begins.

For color contrast, I explore lesser or greater contrasts among colors. Aqua next to turquoise has less contrast than bright red next to yellow or black. Choosing what degree of contrast I want to feature is intuitive, but I also learned how colors interact while at Cooper Union. My teacher called his class ‘Psychology of Perception,’ but the concepts came from his classes with Josef Albers at the Bauhaus and may be called ‘color theory’ by others.

I buy my needles at ordinary stores (Walmart) choosing those that have eyes large enough to accommodate the yarns I use but not so large as to distort the fabric. I use blunt needles most of the time because they damage the fabric the least by slipping between the warp and weft.

I use sharps when I must hit an exact spot and a millimeter off won’t do.

I use thread snips to cut the yarns, and the only yarns I buy are Paternayan 100 percent wool tapestry yarns.

Over the years, these choices have become more unconventional for both practical and stylistic reasons. I rarely get bored with the type of yarn or fabrics I use since the narrative is my main concern. However, the colors I use for skin tones have changed over time.

Usually, I portray African-American subjects. As a result of our history here in the United States, the people we call ‘African-American’ come in all shades between almost shoe-black to the pinkish-white of many European Americans…and all the tans in between. But still, that’s not enough variety for me, so I sometimes want to mix it up and make a green face.

Added together, stitching and color set the mood of each piece and hopefully advance the narrative.

What currently inspires you?

In all areas of my life, I seek the root causes of things and usually find personal issues at the root of the interpersonal. (The impersonal needs of the cosmos may drive the personal but that’s a discussion for a different time.) These personal issues inform the narratives I’ve chosen.

Layered messages in my pieces help meaning unfold over time, hopefully adding value to the visual experience. However, my greatest aim is always toward clarity of communication. Why tell a story if you don’t care if it’s understood?

Beauty is also a major value of mine. Through gracefulness of line and complementarity of color, I find beauty uplifts the spirit. I want it for myself, and I want to pass it on too.

Personal growth is the goal

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

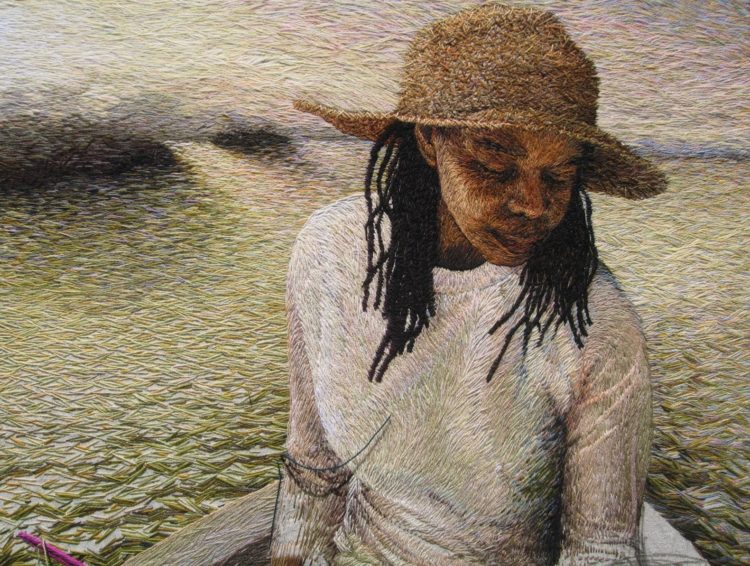

‘Teacup Fishing’ is a piece whose narrative was gifted by the art-gods as a message to me to get my life together. Unfortunately, I chose a model who lived out-of-state. This meant waiting a year or so on two occasions to re-shoot when my drawings needed improvement.

And a change of residence from one state to another caused a separate delay.

It is one of my larger works and size always impacts completion time. But the good thing about time is that it allows the narrative to marinate and deepen. On my website, I discuss the deepening process as it relates to this piece.

I love almost all my pieces like you do your children who grow up to be people with whom you can have a conversation. This one was not the most fun to do, but it has the most to say. It loves me the most.

How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

As an adult looking for a means to earn a living outside of the job market, my art became something technically more complicated but less personal. I borrowed narratives from the general culture, essentially creating a product (‘making art’) rather than letting the pieces be an expression of my inner self.

Adulthood requires one to satisfy so many other people for so long, one becomes estranged from self. All along the way, even in an art career, that’s a danger.

But I kept seeking truth. Since I work essentially alone in a room, I had to look within to find narratives that expressed it.

It might be burdensome, but I feel each of my pieces should be a legacy of some kind. Not so that I can be remembered, but rather that I might be useful. I want to shine a light on some of the pitfalls in life.

Then and now, I also see each creative effort as an opportunity to teach myself better ways to understand how to replicate and extrapolate on my original photographic images–in other words, how to see. This makes the work more nuanced but also more complicated to plan.

I have a few plans for future pieces but am leaving myself open to changing my mind about everything: subjects, style, medium and working methods. I embarked on this career for neither fame nor fortune. Personal growth was my main goal. That requires change, both gain and loss.

All the ancillary skills and strengths an art career requires (independence, courage, public speaking, marketing, introspection, networking, tax preparation, computer literacy, perseverance, organization and more) have helped me immeasurably also. I look forward to continued learning.

What advice would you give to an aspiring textile artist?

Because of its personally transformative effects, I would advise aspiring textile artists to constantly seek greater depth of meaning and technical improvement. Your audience deserves your best, and you will benefit even more than they.

Make corrections to your work if it doesn’t satisfy you. Rip it out. I have no pieces that progressed only forward from start to finish.

Embroidery of any kind is a slow way to create an image, but being prolific isn’t the hallmark of excellence. In fact, neither is wide acceptance. YOU be the judge and be hard to please.

Don’t decide that the best you can do today is now your brand and you have to stick to it. ‘Why’ is my favorite word. If something is working, why does it work? If not, why not? Why is a great guide.

For more information visit ruthmiller-embroidery.weebly.com

Ruth focuses heavily on the narratives of her pieces as well as her techniques. How important is storytelling in your own work?

THANK YOU, Miss Ruth. Your work is inspiring! I hope that one day our paths might cross. Thank you for living your truth, continuing to ask why, and seeking inspiration in “simple” things. May the art gods continue to bless you.

Your work is simply beautiful, heartfelt and inspiring. Thank you for sharing.

Just WOW. Amazing, beautiful work.

This is the most beautiful embroidery I have ever seen….I hope the talented, creative, genius artist Ruth Miller will see this message from me and smile as I did when I saw this amazing work. What a story, what a life and I’m so glad it was shared for inspiration to others. Would be interested in knowing how to get in line for a commission. Many thanks.

This is the most amazing art, not an easy embroidery, just fabulous.

Dear Ruth,

I am the executive director for the Hattiesburg Arts Council and have been enamored with your artwork since hearing about you as the MS Governor’s award winner. We have a beautiful and spacious gallery/community center space at the Hattiesburg Cultural Center that was once a public library built in the early 1900’s. We can imagine your textile work and sketches in this space, and would be thrilled if you would be interested in exhibiting your artwork with us some time in late 2020 or early 2021. If you would like to talk with me about this opportunity, I would be so happy to speak with you at 601-583-6005. (If not here, please leave a message) You can see photos of the Cultural Center on various photos of past exhibits on our webpage http://www.HattiesburgArtsCouncil.org. I would also love to come to Picayune to have a personal viewing of your studio and textile art. Thank you for inspiring so many people with your artwork. I am touched by the story your work conveys. Sincerely, Rebekah Stark Johnson

Hi Rebekah,

I have passed your message on to Ruth via email to make sure she see’s it.

Many thanks and best wishes,

Charlotte

WOW, WOW, WOW …..every ounce in a while I find inspiration in amazing work of fellow artists. This truly resonates with me. Thank you for sharing .

Thank you for sharing your work which is amazing and am inspired by your journey, motivations, and story of what drives your creativity.

This is amazing Art I have seen.

great post keep it up, keep going

Wonderful work, something to aspire to.

Your art work is beautiful. I can only smile when I look at the faces you have captured in thread and needle. Your work truly takes my breath away.

Truly inspiring! Thank you, Ruth.