Mauréna Lambert: Creating through the eyes of the heart

Can mathematics and botany be represented together in textile art? Certainly! Mauréna Lambert is a French textile designer with an insight into this fascinating combination – known as fractals and sacred geometry – and her print and knit-based work in natural fibres is a reflection of this. It depicts primitive lines – the energy lines that she experiences both in nature and other aspects of life.

Born in Paris in 1991, Mauréna was brought up on the island of Guadeloupe in the Caribbean and gained her influences from walking in the creole gardens and along the rivers of Guadeloupe. She later moved to Roubaix where she graduated from the High School of Applied Arts and Textiles and then the National School of Visual Arts of La Cambre in Brussels.

Mauréna seeks out fractals – the never-ending and infinitely complex patterns, often seen in nature, across different scales. They may be seen as symmetries, spirals and stripes and found in trees and plants, meanders, waves, fossils and cracks. Early Greek philosophers studied them in an attempt to explain order in nature, and this study has been continued ever since – both in the science world and in art.

In this interview Mauréna tells us how she developed an intuitive eye for the geometry of nature, how that was nurtured in her grandmother’s garden and how the advent of a new spiritual vision in 2010 influenced the work she does today.

Emotional vision of reality

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium? How was your imagination captured?

Mauréna Lambert: Textile art is a way of speaking without the need to talk. To me, it’s a medium that offers its message as a whisper through your mind. The vast range of textured fibres and patterns, with their structured techniques, that we see all around us were what attracted me to textiles.

The impressionist painters Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet and Odilon Redon, with whom I share the same birthday, attracted me. I like the way they translate their own emotional vision of reality as they see it; their sensibility, feeling of the space, the spontaneous emotional intelligence, the memory. I love the colours and the dreamlike state of Odilon Redon’s painting. Dreams have a special place for me. They are signs.

I like to spend time in our attic digging out old pieces of fabric that I have saved and forgotten about; a piece of arresting, olive green sandblasted silk; a bright lemon yellow embroidered silk with black pleated veil that creates flow in the fabric.

What or who were your early influences and how has your life/upbringing influenced your work?

Growing up, my early art influences were Pierre Soulages, JMW Turner and the sculptures of Alexander Calder.

When I lived on the islands of Guadeloupe and Saint Martin, I took inspiration from the islands’ recovery after the imposing restrictions and the moderation that occurred during the time of the Governor, Constant Sorin (1940-43). Observing that regeneration was very satisfying to me.

I was captivated by the work on construction sites – wrought iron and steel rods and structured buildings. But the most iconic influence from that time was a Kuba fabric that I bought from an African trader from Brussels. Graphically distinctive and richly evocative of central Africa, Kuba cloth is handwoven using the strands from raffia palm leaves. The raffia strands are dyed in a variety of earth tones using vegetable dyes. The cloth can be cut pile or flat woven with no pile, and often features patchwork, embroidery, appliqué and embellishments.

The piece I obtained came from raffia which was woven by a man and embroidered by a very shrewd pregnant woman. I was most impressed by the weaver’s embroidery technique; it displayed perfect embroidery on the top with not one lost thread on the back. I felt humbled and grateful to come across this piece.

I discovered the background of the piece from research I did from Kassaï Productions at the library of the Abbey of La Cambre. There, I had the opportunity of consulting a wonderful book written by Georges Meurant, entitled Shoowa Design: African textiles from the Kingdom of Kuba. He detailed how the preparation of the raffia fibre is done by men.

The embroidery yarn added by the woman gave expression and meaning to the piece, just as I’ve witnessed before in pre-colombian weaving.

What was your route to becoming an artist?

It all began with studying classical applied arts. Then, after completing two degrees in textile design, I had the privilege of practising at the atelier of Augusta Uhlenbeck, a very enthusiastic textile repair expert at the museum, la musée de la piscine, in Roubaix. I also had the good fortune to work at the Sylvie Johnson atelier where I learnt the importance of accuracy.

My best memories are of making bobbins for loom weaving. The repetition of the process to achieve a tight weave, and listening to the mechanical music they made, created abstraction for my mind.

Nomadic simplicity of knit

Tell us about your process from conception to creation

My process of conception starts by defining my subject, and exploring that in every way. It’s like going for a walk up the river. I go over and over it in my mind, until I settle on the fibre and the surface, as I do when working with linen fibres. I am looking for the lines along which my idea can come into creation; for me, it’s like writing the lyrics to a song.

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques and how you use them

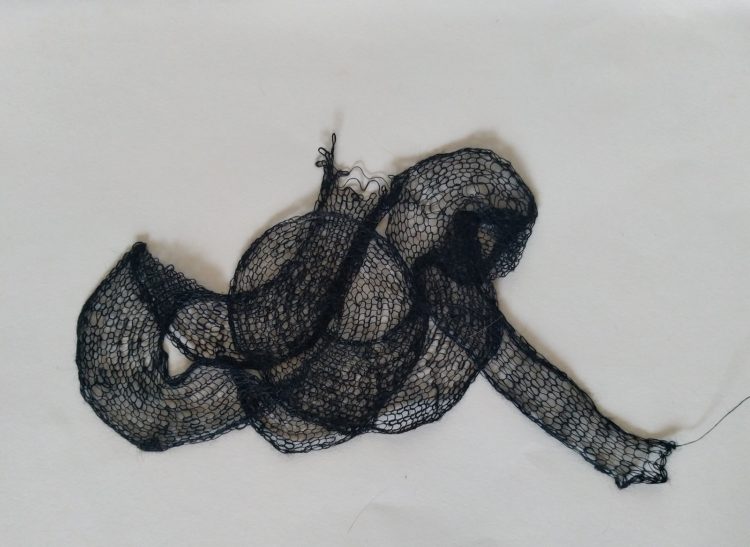

Knit is my main chosen technique – I like it because of it’s nomadic simplicity. I use paper and pen, yarn and a crochet-hook. I also have two old Brother knitting machines from Marianne Redding, with whom I trained.

What currently inspires you?

Currently I am inspired by the history, people and nature that our group of islands shares with the main continent of South America; the richness and diversity of Guadeloupe’s environment, art, people, food and music. Since the 2020 lockdown, I’ve also become more interested in cotton production, in particular the heaviness of the white cotton blankets produced in the 19th century.

Seeing the full and the empty

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

I hold particularly fond memories of a piece I made, that was inspired by the leaf pattern of the succulent plant, Crassula ‘Buddha’s Temple’; its leaves are stacked and folded up at the edges, forming a square-shaped column, and I reproduced this pattern on my piece ‘Crassula temple’.

The photographer, Karl Blossfeldt, was known for his close-up images of plants in which he used lighting to highlight their three-dimensional form. His work was intended to act as a teaching aid and inspiration for architects, sculptors and artists. He believed that only through studying the intrinsic beauty present in natural forms, would contemporary art find its true direction.

Taking inspiration from Blossfeldt’s work, I spent several days sketching, with particular emphasis on the fractals and sacred geometry. I am particularly fond of the mathematics of the botanical world – the infinite and complex patterns, similar across different scales, where a simple process is repeated over and over in an ongoing feedback loop.

I wanted to represent the lines of the succulent plant, crassula’s temple. I became obsessed with my observations of the elementary vibrations of the plant – the kind that I had seen in the Blossfeldt photographs. I think it is more of a meeting between the viewer and the object through the eyes of the heart. As Antoine de Saint-Exupéry says in his story book The Little Prince, “On ne voit bien qu’avec le coeur. L’essentiel est invisible pour les yeux” – “It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye”.

How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

Ever since I began, I have been very literal; I have always wanted to see the reality of things and for my work to be true to what I see. I started with reproducing what I observed in nature; the way that plants, in particular, have such carefully organised pattern structures.

It wasn’t easy to let go of the seeming reality of my own subjective interpretations. Then, during 2010, I experienced the advent of a more monastic, pure and spiritual philosophy in both my life and my work. I think it began with my growing love of working on the land, in particular in my grandmother’s garden. Following that, my vision has evolved so that I can see both the full and the empty, and I continue, today, to experiment with this creative concept.

For more information visit www.maurenalambert.fr/ and Instagram

Has Maurena’s story inspired you to try a different approach to your textile art? Let us know in the comments below.

Thank you for yet another fascinating interview. What intriguing work: how helpful the commentary is in giving us insight into the visual patterns. Thank you and the artist for your generous sharing

Marena’s work is both beautiful and inspiring….and I respect her interest in fractals and sacred geometry since both are important to me, and have been for most of my life. Both of these are related through repetition and pattern. At this very moment I am experimenting with stitching an octagon which contains rectangles, squares and and triangles plus a smaller octagon. And it is all enclosed within a circle! There is both mystery and revelation when one works with these forms.

Your work in sending out information on the work of textile artists has kept me going during lock downs and is so much appreciated. Thanks also to the many artists you are featuring….their work is reassuring exciting and inspiring.