Richard McVetis: The act of making

The muted tones and simple stitches employed by Richard McVetis in his embroidery work have become a hallmark of his practice. The outcome has a pleasing minimalist aesthetic and is an important part of the story. But what’s more significant is Richard’s drive to go beyond the surface detail and ask questions about the very act and process of embroidery.

From stitched cubes exploring the concept of time, to personal narratives, which delve into his family history, a meticulous technical methodology always underpins his work. For Richard, embroidery has become a form of meditation, and a conscious study of the act of stitching.

Captured by the process of embroidery

TextileArtist.org: Tell us about your process…

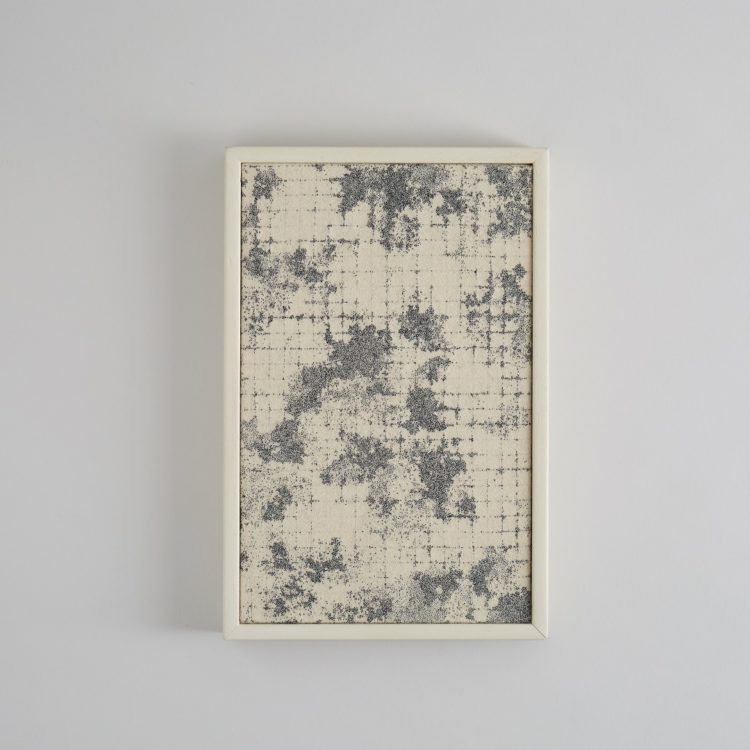

Richard McVetis: My artistic practice centres on my training as an embroiderer, through the use of traditional hand stitch techniques and mark making. Laboured and meticulously worked wools, stitched with multiples of embroidered dots and crosses, explore the similarities between pen on paper and thread on fabric.

Each stitch or line acts as a marker for time lived, and becomes an embodiment of thought and patience.

By using a limited vocabulary of mark making and deliberately subdued colour, I’m able to create a binary simplicity. These physical, tactile and repetitive modes of creation allow me the time to visualise, consider and occupy a space.

What inspires you?

Mapping out space, marking time, and form are central themes. My ideas are often developed in response to a moment – to visualise and transform time or a place into a tactile and tangible object.

I’m inspired by the process and the act of making, and its ritualistic and repetitive nature.

Many of the patterns that appear in my work are inspired by rarely noticed everyday marks, like the metal tread of a station entrance, or the shadow created by the morning sunlight. By taking notice of these, and removing them from their context, I’m able to elevate the mundane to a higher status.

My fascination with textiles and the recording and communicating of time, started with my early work, My Grey Pencil Case. It was created by unpicking the seams of my Royal College of Art pencil case. The case revealed drawings and marks on the inner surface, such as the pen and pencil marks, which had secretly recorded the rhythms of daily life. Here I could see the abstract trace of my body’s movement over a period of years.

This work directly inspired the cubes in my subsequent series Units of Time, and then Variations of a Stitched Cube, where I measured time and physically represented this invisible force using stitch.

A framework of sixty

What was the idea behind Variations of a Stitched Cube?

My series of embroidered cubes, Units of Time, was the starting point for Variations of a Stitched Cube, a sculptural work.

This project was inspired by the origins and methods of measuring time, as well as the work of the American artist Solomon ‘Sol’ LeWitt. LeWitt’s 1974 work Incomplete Open Cubes explored the geometry, intrinsic nature, and perception of the cube as both a complex and playful shape. The viewer could consider each cube individually, but the work as a whole has a repetitive but varied style, with an almost obsessive quality.

Alongside LeWitt’s work, I researched the measurement of time, which is based on units of sixty, using the sexagesimal system conceived by the Sumerian civilisation. There are sixty seconds in a minute, and sixty minutes in an hour. The Sumerians also had a calendar with 360 (60 x 6) days in a year.

The number sixty became the framework for my project.

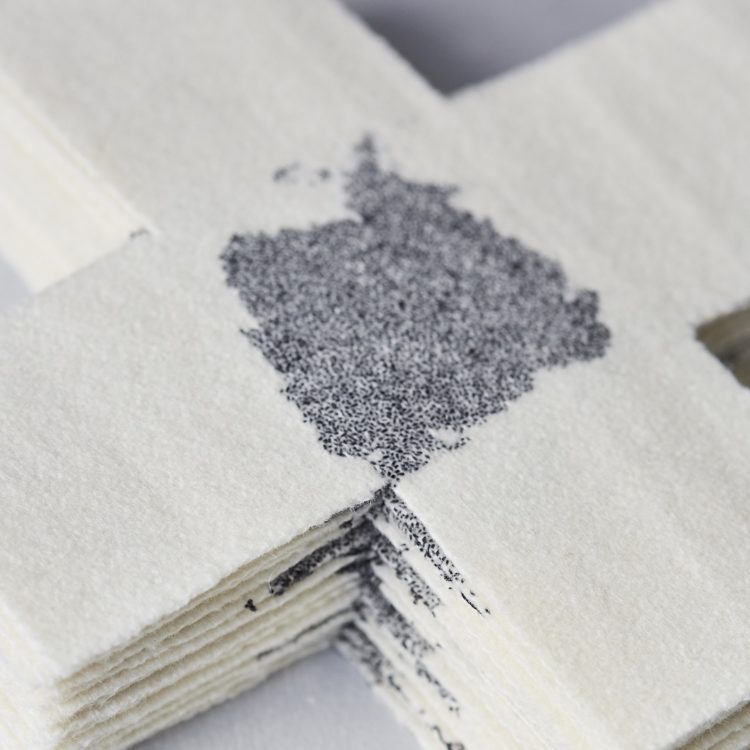

Each of my stitched cubes measured sixty millimetres in each direction. The cubes were shown in sequence, each recording time through collections of embroidered dots measured in increasing and enforced increments of one hour.

The sequence started with the first cube, which I stitched for sixty minutes, and finished on the sixtieth cube, which I stitched for sixty hours.

The cubes were presented as one installation, initially installed on individual podiums that were conjoined at the base. The work has since evolved to be displayed on a table, and was part of my solo exhibition, Shaped by Time, in Farnham 2022.

The presentation of this work as a sculpture was integral. It marked a departure for my practice, allowing me to take my work from the wall to the centre of the gallery. I was interested in how I could affect a three-dimensional space with small objects.

Timed embroidery

And how did you create the work?

I wanted the cubes to show time, an ever-present invisible force, through a form that was both logical and playful, created through the random process of hand embroidery.

The cubes’ variations imply and manifest the passage of time.

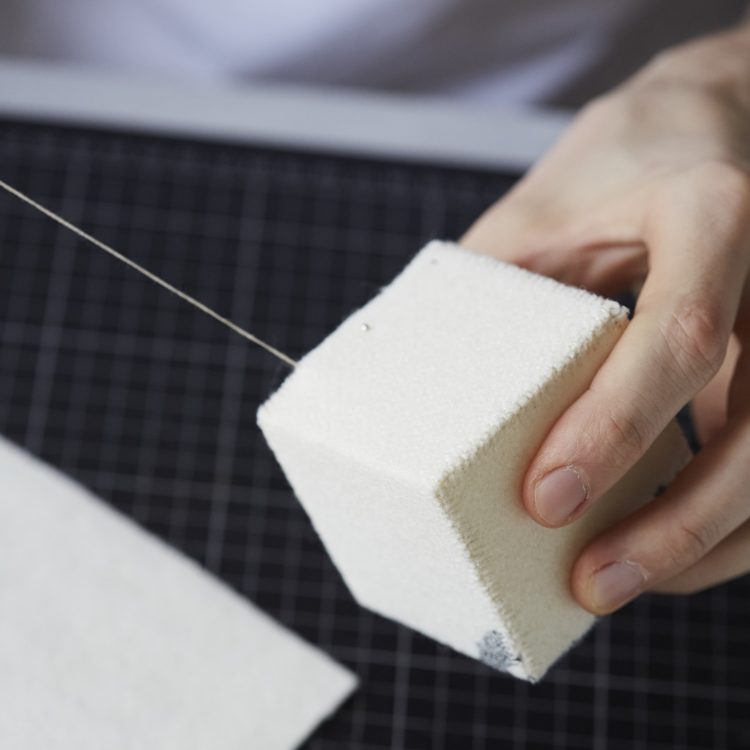

I used materials I was already familiar with: a heavy wool flannel fabric, cotton thread and Styrofoam cubes formed using a hot wire cutter. I created a net pattern in Adobe Illustrator, which was printed onto dye sublimation paper and transferred to the fabric using a heat press.

The longest part of the creative process was the timed embroidery of each individual cube.

I used seed stitch, starting at the same point each time, then stitching freely until the allotted time was up. During this period of making, I became hyper-aware of time. Time seemed to slow down to the point where ten minutes felt like an hour. As the time increased for each cube, I went through a roller coaster of emotions.

Embroidering for longer and longer periods had an effect on body and mind. The physicality and mental stamina required for this project really took its toll.

After I’d completed the embroidery, I cut out the net patterns, folding them over the Styrofoam cubes and carefully suturing the edges. This was probably my favourite part. My mini maps of time flowed up, down and around the cube, to create something completely random. The two-dimensional patterns took on a whole new life.

How has your work evolved?

My work has gone through various stages of development, from two-dimensional to three-dimensional, non-stitched and heavily stitched, and incorporating film and installation.

Process and making always form the main narrative, but reading and researching have become a more integral part. This has led me to exploring physics and philosophy. More recently, I’ve started a series of works with a more personal narrative, retracing my family history to a time and place.

While the themes and ideas change, I enjoy taking quite a simple process and arranging it in infinitely different configurations, enabling me to describe something that I can’t easily communicate with words.

Stitching a narrative

Tell us about your work exploring family history…

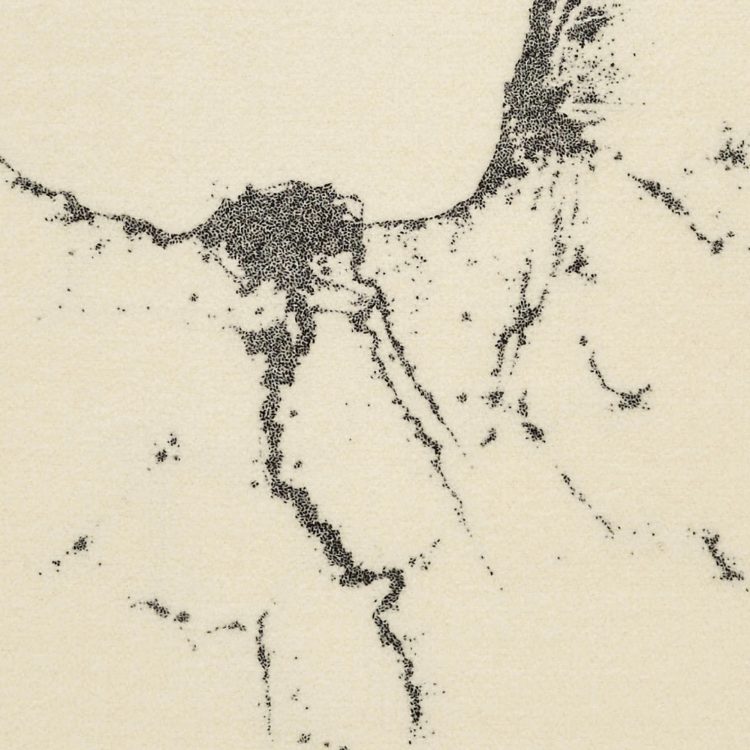

In 2021, the British Textile Biennial theme focused on the global context of textiles, textile production, and the relationships it creates, both historically and today. The exhibition took place in various venues across Lancashire, the birthplace of the cotton industrial revolution. In response to this brief, I created two new works, A Portrait of Coal and Coal Seams.

Coal’s importance in the cotton industrial revolution cannot be understated. It was vital to Lancashire’s dominance of this industry; wherever coal was, change happened. Coal left its mark and defined this country, and the world, and will continue to do so for decades to come. The textile industry funded growth: towns grew from nothing and people came from worldwide.

Arriving in Scotland at the beginning of the twentieth century, my family took up work in the newly opened Lady Victoria Colliery in Newtongrange, Midlothian, Scotland. The colliery site was chosen because of its proximity to the Waverley Railway Line, making it an ideal location for transporting coal to the textile mills in the Borders.

My dad began his mining career at the age of sixteen, a forty-year career that saw him mine the coal seams in Scotland, Staffordshire and South Africa. The politics and deindustrialisation in the 1980s resulted in my parents emigrating to Witbank, South Africa, where I was born.

The pattern pieces printed onto the fabric are those of the first miners’ coat, designed and conceived in Rugeley, Staffordshire, my mom’s hometown, and the place we returned to after ten years in South Africa. The donkey jacket became a symbol of the British manual labourer and the political left.

Using a labour-intensive hand embroidery process, Coal Seams maps the hidden underground landscapes of this elemental material, formed over three hundred million years ago. It brings a story of race and class to the surface. It examines my family connections to materials and places, and how, like the seams that shape a garment, coal continues to shape our lives.

What first attracted you to embroidery as a medium?

It began on my foundation art and design course. Inspired by the passion of my tutor Amanda Clayton, it was here that I was able to see the potential of textiles as a medium for artistic expression.

While visiting an open day for the embroidery degree at Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU), I became aware of how embroidery could become a form of expression.

What attracted me was the chance to learn one of the world’s oldest crafts, while exploiting its contemporary possibilities at the same time.

After my foundation year, I studied for an embroidery degree at MMU and then I became an Embroiderers’ Guild Scholar. Following this, I took a year out from education and then headed to the Royal College of Art.

I find the diversity and exploration of the medium liberating. During my studies, my imagination was truly captured, and through great tutelage, I was able to develop my own style.

How do you make the most of being a member of the 62 Group?

Being part of the 62 Group is a chance to be part of a community. An artist’s life can be lonely and very insular, therefore it’s vital to have conversations and support fellow artists who understand what you might be going through.

I joined the group in 2015. Since then, I’ve taken an active role, joined the committee and became the exhibitions officer. I’m responsible for the overall coordination of the exhibition programme, most recently the group exhibition at the British Textile Biennial.

Taking an active part allows me to meet all the members and network with institutions and galleries. It’s also a chance to shape and build a progressive and diverse community.

In 2022, the group celebrates its sixtieth birthday, and I’m very aware of our responsibility to honour and maintain the legacy and work done by those who came before.

What piece of equipment could you not live without?

I like the honesty, simplicity and accessibility of hand embroidery. I’m lucky that my practice doesn’t rely on any complicated tools: it means I’m able to create wherever I go. All I need is a needle, fabric and some black thread.

My camera is also essential. Most ideas begin with things I see when I’m out and about. With a camera, I can record these moments quickly so that I can review them at a later date.

Key takeaways

We often focus on the end result, but here’s some other ways to get more out of your embroidery:

- Richard’s stitches mark the passing of time. How might you place the focus on the physical process of embroidery in order to gain a deeper connection to your work?

- Embroidery art can be taken away from the wall by filling a space with small objects to create a sculpture. Think about ways of taking your embroidery into three dimensions.

- Mark making is a great way to create maps, as Richard has done while exploring his family history and connections to places. What story could you tell using different embroidery stitches as marks?

Artist biography

Richard McVetis is a member of the 62 Group of Textile Artists. He has been shortlisted for several prizes including the Jerwood Drawing Prize (2011 and 2017) and the international Loewe Craft Prize (2018) and is a visiting lecturer in Textiles at the Royal College of Art, London.

He exhibited at The British Textile Biennial (2021), RENEW at Kettle’s Yard (2019), Collect Open at the Saatchi Gallery (2017) and Form + Motion at the Cheongju Craft Biennale, South Korea (2017). In 2022 Richard staged his first solo show at the Craft Study Centre, Farnham.

Website: richardmcvetis.co.uk

Facebook: facebook.com/richardmcvetisart

Instagram: @richardmcvetis

Learn more about abstract art in Delightful distortion: Seven abstract textile artists. And if you are interested in other ways of using mark making to depict time and place, read Vanessa Rolf’s interview Stitching Connections.

If you enjoyed reading how Richard places focus on the physical act of stitch, share this article with your friends. It’s easy – simply click on the buttons below.

Hi Judith, just enter your e-mail address and hit the yellow bar. Do let us know if you continue to have problems.

I love!!!! your minimalistic work

pnina vitaly

I love the sense of calm that lies quietly waiting for further looks. It’s obvious the time it took, but as a “Zentangler” it isn’t about the time spent on a piece, it’s about the peace that rests in the time you spent. Huh. I wonder where that came from. It just drifted through the keys of my keyboard and ended up on the screen.

Anyway, I would hope that someone would look at my work someday and get that same sense of calm.

Look for Richard’s work in my book, Dimensional Cloth: Sculpture by Contemporary Textile Artists, released by Schiffer this week (July 2018)!

Love this work and great interview to read, thank you

During a bout of insomnia, I found this interview and really enjoyed it.Thank you!

I have admired Richard’s controlled minimalistic works for a long time, probably because it is the total opposite of my own over the-top textile artworks.

As I am a South African by birth I was excited to read that he was born in Witbank. Another well-known international artist, Diane Victor, was also born there. So, that coal mining area has spawned some great artists.

Congratulations Richard love your work.

Best regards,

Celia