Vanessa Marr: From conception to creation

Artist and lecturer Vanessa Marr thrives on collaborative projects, and plays an active part in the textile art group unFOLD. In a series of pieces created for the Festival of Quilts 2018 exhibition, group members took inspiration from The Button Box, by Lynn Knight, a book about women in the 20th Century, told through the clothes they wore.

The post-war period was a time when women were pushed back into domestic life, after the Second World War. For this project, Vanessa used text and images from real advertisements from around that time, and hand embroidered them onto vintage dressing-table cloths and garments. With a background in graphic design, the illustrations and accompanying absurd text of these adverts really attracted her.

At first she set out to subvert or change the text in some way. But she often found the adverts so ridiculous she didn’t need to change them at all, to make a statement.

Through this work, Vanessa wanted to connect the ‘feminine’ art of embroidery with the declarations of female perfection that was, and still is, presented in the media. Her embroideries highlight how these expectations of the ‘perfect woman’ still exist today, and that little has changed since those vintage adverts were first published.

Each part of Vanessa’s work, the selected objects, the process of hand stitching, and the embroidered outcomes, are intended to reflect both the powerlessness and the pleasure of being a woman, whilst challenging the patriarchal perspectives on the female body.

The perfect woman

TextileArtist.org: How did the idea for the work come about? What was your inspiration?

Vanessa Marr: The inspiration for my work comes from references made to beauty advertising, which were discussed throughout the book, The Button Box.

It struck me that the advertisements positioned a woman as a figure who should apparently always be striving for physical perfection, whilst seeking to get, and then keep, her man. Just as the choice of button displays and presents a variety of visual messages depending on its size, colour and style, so does a woman’s beauty product choices.

The work was made of several different pieces:

As long as you’re beautiful!

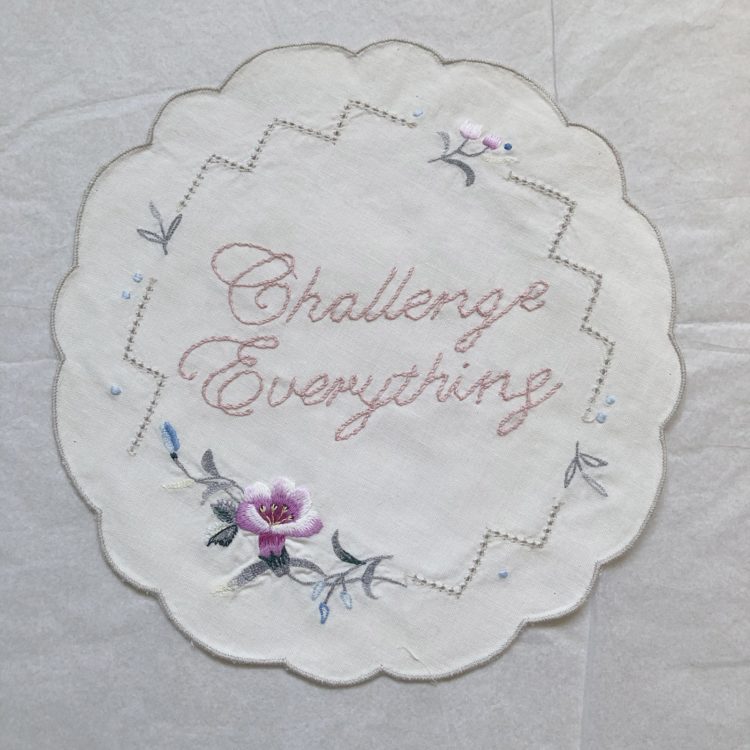

This collection of hand-embroidered vintage dressing-table cloths explores the idea that a quilt, in its most basic form, is a collection of different pieces of fabric pieced together to form a whole. By isolating individual words and phrases, taken directly from make-up advertisements from the 1950s, the messages are ‘quilted’ together and the absurdity of the language is highlighted.

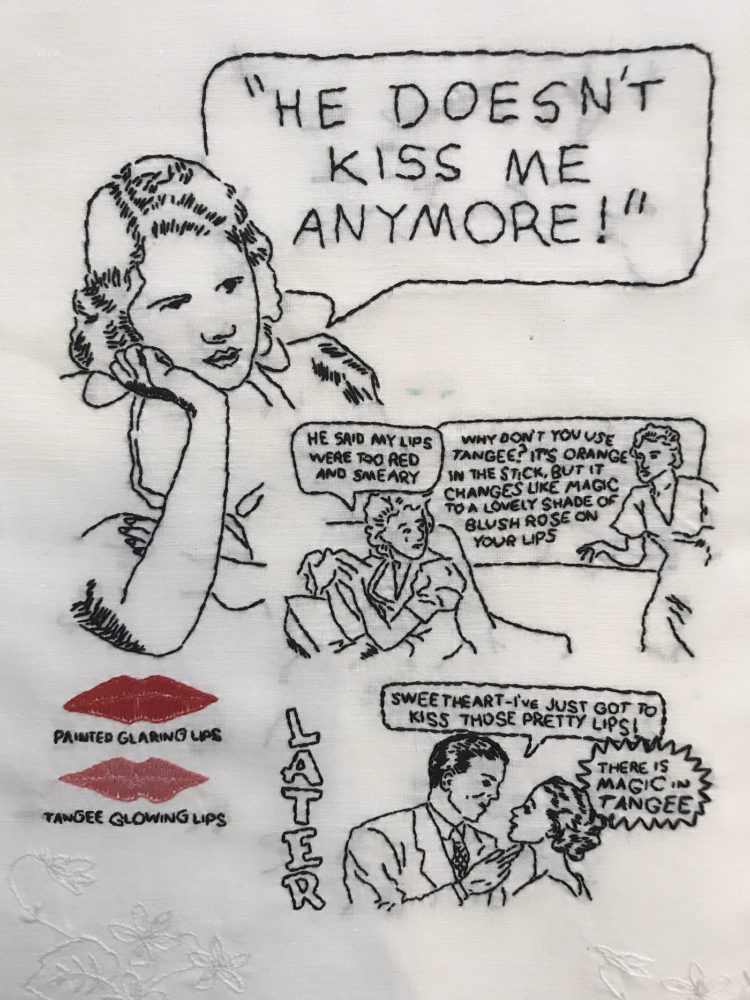

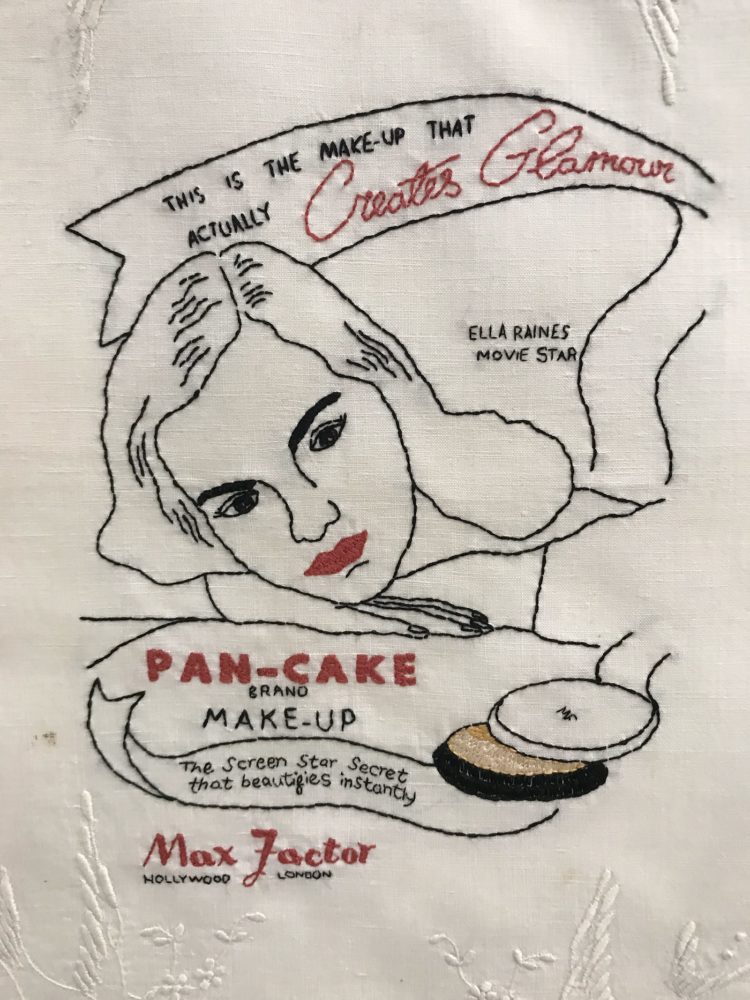

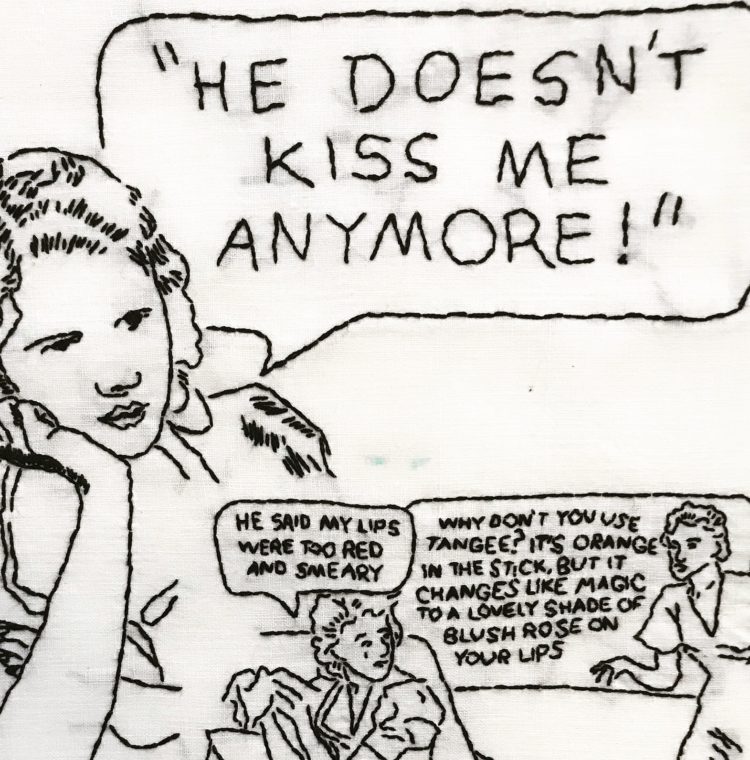

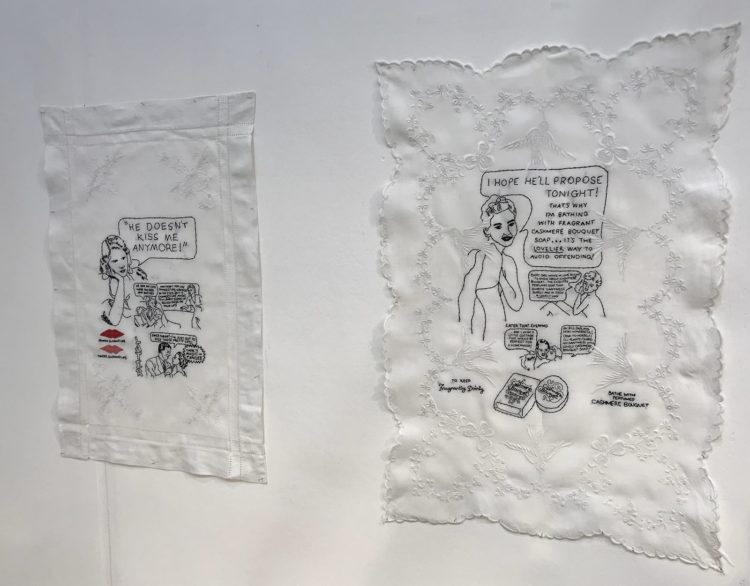

Ways to get your man…

These are exact copies of real adverts. I discovered several more with a similar theme. In each narrative the girl is offered a magic potion that will ensure her success in ‘getting her man’. Lipstick or soap solve the problem in these examples, but it’s a small step to the magic potions of fairy tales. These narratives set the tone for expected behaviour, as well as appearance.

Feminine Niceties

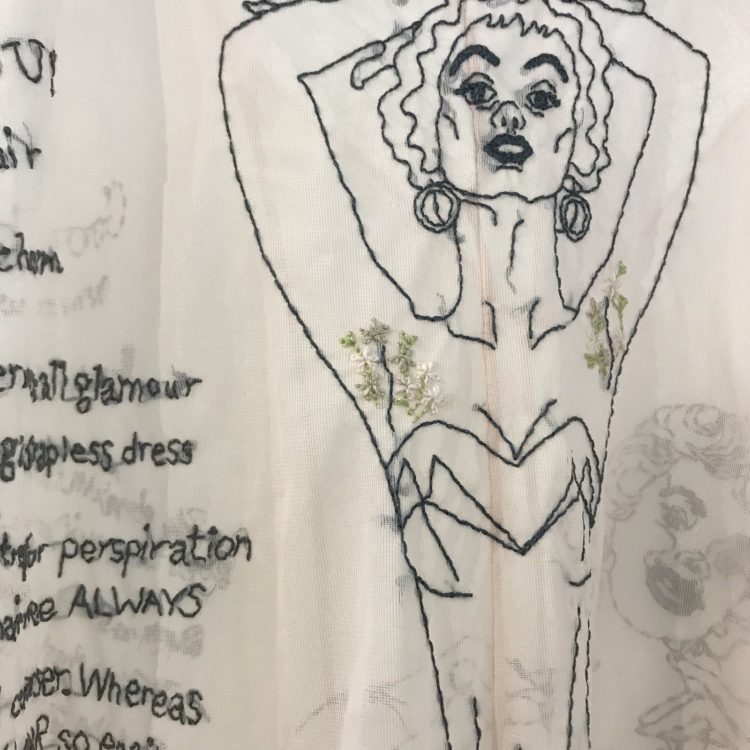

Women are expected to do things to their bodies that are contrary to the natural state of things, for the sake of appearing ‘feminine’ and ‘nice’. Advertising has made this so normal that we often don’t question it.

For the Feminine Niceties collection, I chose vintage night dresses or slips. These items of clothing are not actually necessary, yet they perform the purpose of making the woman become more ‘visually appealing’. I selected ‘normal’ changes that we make to our bodies, such as the removal of body hair, wearing underwear that impacts our shape (even the modern bra still does this), and dieting.

The pale pink nightie features the alarming text I found on an advert for Veet hair removal cream with women who had flowers embroidered under their armpits. A flouncy, yellow slip told girls ‘not to be skinny’ (this was an exact quote), whilst the third, slightly more fitted version, extolled the virtues of a ‘sweetheart figure’.

What research did you do before you started to make?

After reading The Button Box, I bought several vintage magazines from eBay. Through these, I explored the work of popular illustrators from this period, like Norman Rockwell.

I also read various academic books about the language and visual meanings of adverts from the 1950s, which provided a deeper understanding.

Subversive messages

Was there any other preparatory work?

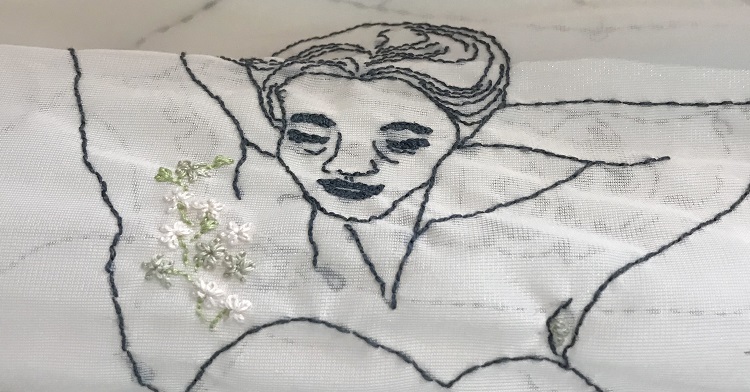

Before I started stitching, I practised illustrating the 1950’s style figures that I wanted to embroider.

Also, I explored the use of dissolvable fabric. I decided to use this fabric to support the work when I embroidered the ladies onto the night dresses, as the fine nightwear didn’t take well to my erasable pen and was too slippery to stitch directly into. When I had finished stitching, the dissolvable layer could be simply washed away.

What materials were used in the creation of the piece?

I had great fun finding vintage textiles to work on. I searched eBay purchases for vintage cloths, and found a set of night dresses in a local charity/thrift shop. I purchased some dressing table items from this era, to support my exhibition display.

I chose the cloths based on their size and shape.

For Ways to get your man, the cloths featuring an entire page sized advert, I found some large rectangular cloths with white stitched embellishments that would frame my embroidery work. The set of three cloths were approximately the same size, so I knew they could be exhibited together as a collection.

I used small, circular cloths for As long as you’re beautiful. These were like lace doilies, but with a clear, flat space in the centre that I could embroider. I chose a range of embroidery silks for my stitching, in colours that suited the designs that the cloths already held, with red colours for the lips. The text I chose refers to various makeup or beauty products. I displayed the works together like a ‘quilt’ of messages. I also slipped in a few of my own subversive messages, like ‘Rebel often’.

The night dresses I selected were of different, but complimentary, colours. I also borrowed and bought padded hangers to display them on, to support the feminine theme.

What equipment do you find useful when creating your embroideries?

My favourite tool is my much-loved erasable fabric pen. I use this to trace or draw the text or illustration directly onto the cloth.

For this stage of my work I find a lightbox helpful to trace designs. This approach comes from my background as a graphic designer and illustrator.

Once I’ve traced or drawn my designs, I stretch the fabric into a hoop and ‘draw’ these lines by hand in back stitch using stranded embroidery thread.

In the case of the night dresses, I drew directly onto dissolvable fabric, which was then placed over the night dress fabric, ready to stitch. Sometimes the lines I draw on dissolvable fabric don’t give me enough detail, so I use them as a guide. I stitch freehand over the top of them, to get features like the eyelashes looking just right.

Stitching on the train

When and where do you stitch?

The process of hand embroidery is slow, so I often carry my work around with me. I stitch in spare moments, such as when I am commuting to work on the train. I even stitch while sitting on the beach, sometimes.

I got some funny looks when I took out my nighties and started stitching on them.

Once a man on a train asked me if I couldn’t think of anything better to do with my time! (No, I couldn’t.)

What journey has the work been on since its was created?

These works were exhibited at the Festival of Quilts 2018.

The Veet hair removal cream night dress and the Cashmere Bouquet soap ‘Ways to get your man’ cloth were both selected for an exhibition at the University of Brighton, where I am a lecturer. This exhibition, Imaginative Objects: Reading the Image in Research, explored how practice-based academics, like myself, make work with objects as part of their research.

The works also influenced the embroideries I made after my hysterectomy in 2020, which used the same style cloths to anchor my visual commentary about feminine concerns.

Key takeaways:

- Making use of simple tools and materials like dissolvable support fabric or an erasable fabric pen can be help you to handle your textiles and get the details just right.

- Sometimes the message you want to communicate is staring you right in the face. Many of the 1950s adverts Vanessa used already made a statement, without needing any further subversion.

- It’s good to accept that hand embroidery is slow. Just find those quiet moments to stitch, whenever and wherever you can.

About the artist:

Vanessa Marr is an artist and lecturer, with a background in graphic design. She is a lecturer at the University of Brighton, UK, Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts (RSA), and a member of the unFOLD textile group.

Best known for her embroidered works on yellow duster cloths, Vanessa is also the founder of the ongoing collaborative project, Women & Domesticity – What’s your Perspective?, inviting statements (embroidered on dusters) exploring the theme of domesticity.

Website: https://marrvanessa.wordpress.com

Instagram: @vanemarr

Did some of these nostalgic adverts make you smile? Why not share this interview with your friends using the buttons below.

Dear Vanessa Marr,

I love very much all your fantastic embroiderises.

I would like try some similar – of course I doesn’ think imitation your works.

Thank you very much!

Wish a Happy New Year!

Best

Marianne