Michael James: A visceral connection with textiles

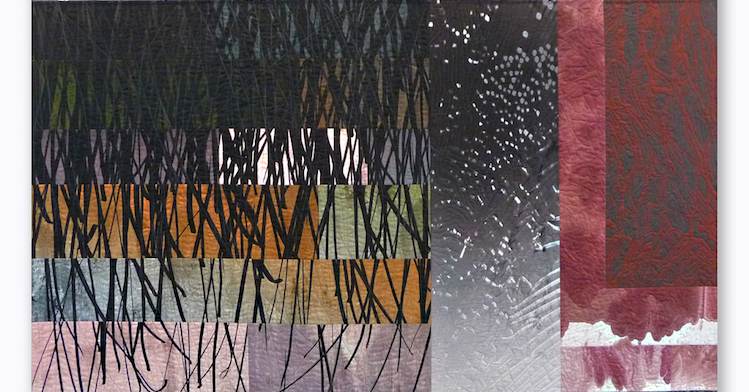

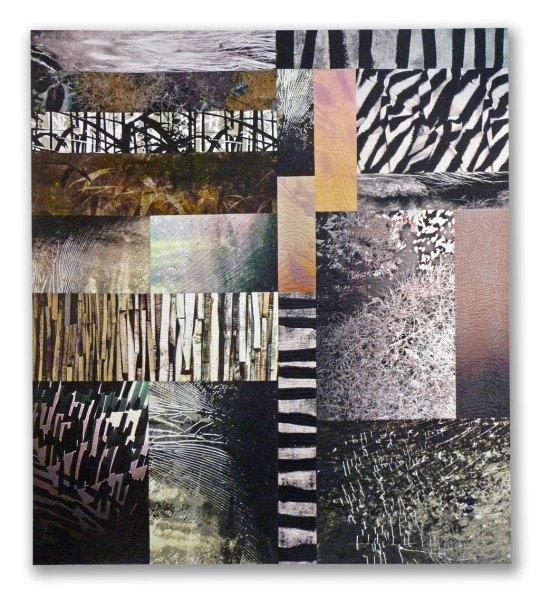

As a leader of the artquilt movement that began in the 1970’s, Michael James has become one of most distinguished voices in the medium of quilted fabric construction. His work explores the fluid borderline between the physical and metaphysical world. More recently, he’s addressed the universal question of mortality and grief, and what it means to live, to love, to lose and to remember.

Michael James chairs the Department of Textiles, Merchandising & Fashion Design at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL), where he holds the Ardis James Professorship and teaches graduate courses in the area of quilt studies. His textile art is included in the collections of the Museum of Arts & Design in NYC, the Baltimore Art Museum, the Racine Art Museum, the Newark Museum, the Mint Museum, the Indianapolis Museum of Art, the Shelbourne Museum, the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution, and the International Quilt Study Center & Museum (IQSCM) at UNL, among others. His most recent solo exhibition Ambiguity & Enigma: Recent Quilts by Michael James hangs at the IQSCM through February 20, 2016. His work is represented exclusively by Modern Arts Midtown in Omaha, Nebraska.

In this interview Michael talks about his early life growing up in Massachusetts, his strong family links to the textile industry there and its decline. He provides a fascinating insight into how he works and we also discover how personal tragedy shaped and inspired his latest exhibition.

Immersion, from an early age

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium?

Michael James: I was already making with textiles before I thought of them as a ‘medium.’ My undergraduate and graduate studies in fine arts were focused on painting and printmaking. I began my interest in quilts and related arts while finishing my thesis work for my M.F.A. at Rochester Institute of Technology in Rochester, NY. One thing led to another and in short order I’d abandoned painting in favor of quiltmaking. I suppose there was some visceral connection with textiles that was stronger than any I’d felt for painting or printmaking. Interestingly, all of my work today is based in digital textile printing technology, so as they say, ‘what goes round, comes round’.

And, more specifically, how was your imagination captured by quilts?

Like most people who become interested in quilts and quiltmaking, I was intrigued by the long and varied history – many centuries’ worth – that had largely passed the notice of the art establishment, that existed outside the mainstream of art history. This was ‘women’s work’, so historically it had been easy to dismiss, to relegate to the more or less invisible domestic sphere, to the work of ‘anonymous’. The rich expression and visual authority that I discovered in these objects subverted any narrow assumptions I might have had about what these works were, and I was hooked.

The heyday of the textile industry

What or who were your early influences and how has your life/upbringing influenced your work?

Only in hindsight have I come to realize that the source of much of my interest in textiles lies in my family’s connections to the textile industry and in its numerous histories. When textile manufacturing constituted the economic backbone of many New England cities and towns, my great-grandparents emigrated from rural Quebec and from Preston, Lancashire to labor in the textile mills of southeastern Massachusetts, in one of whose shadows I grew up.

I was born and raised in New Bedford, MA, and while still a child I saw the slow disappearance of the last vestiges of the New England textile industry which, by the late 1950s, had completely collapsed. That collapse dramatically altered the economic landscape for the working class who had been employed in those mills, my parents and grandparents included. Their stories of the textile industry’s heyday became a familiar family narrative, that I now believe cemented my interest in its history, culture and its technologies.

My parents, neither of whom completed high school, strongly supported my ambition to complete an undergraduate degree, which I pursued at what was then Southeastern Massachusetts University (today it’s the University of Massachusetts/Dartmouth). That school’s history went back to the heyday of the textile industry in that part of the country. It was formed by a merger of two textile institutes, and still has strong textile engineering and textile technology programs.

What was your route to becoming an artist?

Immersion from an early age. I always knew that I wanted to be an artist, though as a child I didn’t really understand what that meant. Nonetheless, I was able to imagine what a life in art could be like, and I never really looked elsewhere. Creating that life was a matter of doing the work, and that was always such a pleasure that it more or less took care of itself. I loved making – still do – so it was, literally, following my bliss. I see many of our students today struggling with questions about careers and ambitions, and being unclear about what they are passionate about. I was lucky, that was never a question.

Listening for the work to respond

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques.

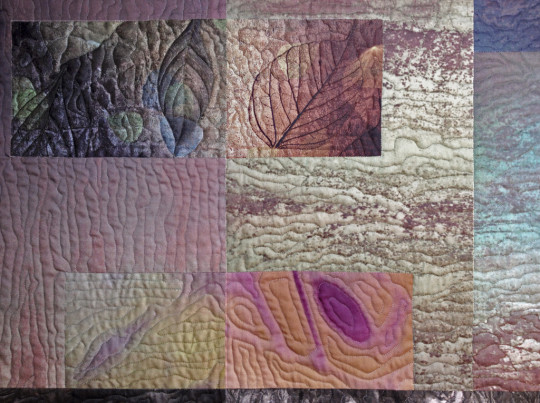

In my work of the last decade I’ve concentrated on using a variety of techniques to develop surface imagery. But regardless of the method I choose, the processing is digital, that is, images are scanned or otherwise imported into design software and then manipulated until I arrive at the ‘look’ or color or textural qualities that I have in mind. Working this way, I have unlimited options in terms of color adjustments and in regards to size and proportional changes.

The images are then printed onto a cotton substrate (either broadcloth or sateen) with reactive dyes, working on a Mimaki DS1600 digital textile printer. The pre-treated fabric readily accepts the dyes, and a post-printing steaming procedure fixes them permanently. The final preparatory step involves washing the fabric at a high temperature with mild detergent, followed by at least two cold rinses. This helps to eliminate excess dye and returns the fabric to its original suppleness. It then joins my studio ‘working stock’ or is directed into a work-in-progress.

The way I’ve been working since 2002, my pieces develop both through planning and through spontaneous engagement with the materials and processes. Since I create all of the printed fabric that I use, I invest a fair amount of time in planning and developing those fabrics. This part is a bit more calculated and purposeful. Once I get the fabrics in my studio, I begin to play with them, usually without a fixed idea in my head of what the end result will look like. I don’t do a lot of sketching, although I will make simple diagrams to work out size and scale problems. I like to get the fabric on my studio wall and then enter into a dialogue with it. I do something, then I step back and take in what’s there. I listen for the work to respond, and then I respond in turn. It’s a dialogue, and if I’m really listening the result is usually a work that reveals a certain rightness and integrity. At least that’s the goal.

How do you use these techniques in conjunction with quilted fabric?

Well, the quilting, which my studio assistant Leah Sorensen-Hayes carries out – I create and construct the tops of my quilts, and she quilts and binds them – provides the physical texture that defines the object as a quilt. The pieced tops are visual compositions but they have a kind of flatness until they’re quilted. In that state they lack richness, substance. The quilting is a kind of laborious mapping of the topography of the piece, and a process of deep connection with the object. I pieced and quilted all of my work myself for over a quarter century, so I’m intimate with these processes. I think that fabric holds energy and memory, embedded during those long hours guiding it under needle and thread. Leah proved over a dozen years ago that she could sort of ‘channel’ me in the process of quilting. She was quick to learn how I saw and did things, how I wanted particular processes to be executed, and she has remained faithful to my vision of how I want the objects I create to be.

Quiet reflection to seizing the moment

How would you describe your work and where do you think it fits within the sphere of contemporary art?

I make quilts. That admission is, unfortunately, damning in the contemporary art world. The favored term in use among folks who are a bit skittish about ‘the quilt world’ is mixed media. Well, that’s fine, if maybe a little pretentious. A quilt is a quilt is a quilt. From the beginning I’ve located my work in the flow of the history of quilts and related arts. I’m fine with that. Certainly, there’s some ambiguity here: he’s a man, and he makes quilts? And they don’t look like what you think of when you hear the word ‘quilt’. And he doesn’t quilt them himself, a woman does that. Hmmm… I don’t lose sleep over these perceptions and misperceptions. I just do the work.

Do you use a sketchbook? If not, what preparatory work do you do?

As I said above, I don’t do much sketching, though I might pencil out different schematic arrangements for a piece in the early stages. I’m comfortable engaging with the fabric directly on my studio wall, and that’s where the trial and error part plays out.

My prep tends to be other kinds of activity – quiet reflection, looking out at the lake on which I live, reading, writing poetry, going for a long bike ride, sometimes organizing things in the studio, looking through my fabric collection, opening myself up to whatever possibilities are going to present themselves on a given day. I’ve always worked impulsively and intuitively, so when ideas come I seize the moment; other times, I remain patient and attentive.

What environment do you like to work in?

I can only make objects in my studio. Right now my primary studio is in the building on campus that houses the department that I chair. It’s a bright windowless room in the basement of the building and is cocoon-like: quiet and isolated. I’ve always needed quiet and isolation from distractions to work, and this space offers that. While I do listen to music while I work – a lot of Bach, sometimes opera, sometimes solo acoustic instruments via online radio – I need otherwise to be alone in that space to make the time productive. Leah and I have learned over the years how to schedule our time there so that we stay out of one another’s way.

The experience of ambiguous grief and loss

What currently inspires you?

I’m just coming out of a long and difficult personal journey. In 2009 my textile artist wife Judith was diagnosed with younger onset Alzheimer’s disease, and our lives were upended in major ways. By 2013 I’d figured out how I could address the experience in a thoughtful and concentrated way in my work, and began what would be a two-year studio effort to explore this experience of ambiguous grief and loss. It culminated in the show of my work now hanging here at the International Quilt Study Center & Museum, Ambiguity & Enigma: Recent Quilts by Michael James. There are fourteen new works in the show, documented in the catalogue that the IQSCM produced, that includes essays by former Art in America editor Janet Koplos and myself (www.quiltstudy.org) .

Judy died in mid-August, of complications from the disease. I haven’t had much interest in being in the studio since the last of the pieces for the show was completed in early May. These past months my creative work, such as it is, has been writing: some poetry, an online blog about our experience since Judith went into hospice care near the end of May, journal notes and reflections. I’ve been putting a lot of creative effort into organizing her memorial service, which will take place in mid October, and in planning toward a memorial exhibition of her work that will hang in the Quilt Center here for the week leading up to her service. Once all this is behind me, I’ll be open to whatever comes my way in terms of inspiration. Or not. Grief is unpredictable and difficult, maybe impossible, to control. For the time being I’m giving myself to it.

Who have been your major influences and why?

Too many to mention. I will say that they come from every direction, from numerous and varied media: music, fiction, non-fiction, theater, visual arts, dance… the list goes on. I’ve lived a life immersed in the arts, and that’s been hugely rewarding in terms of fertilizing my own work.

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

I’m not feeling particularly nostalgic in this regard at the moment. When asked about my favorite work(s) – a common question – I usually reply that it’s the work I’m currently working on or that I’ve most recently finished. That may be a kind of cliché, but it’s true. My mind right now is entirely connected with the works in my current show, because they came out of those years of care-giving that taught me what love and compassion are really about. They’re probably the most autobiographical works I’ve ever made, or am ever likely to make.

Do what you love, and love what you do

How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

Actually, my interest right now is in writing, especially poetry, and it’s something I see myself doing with more purpose and concentration going forward. I’m about five years out from retiring from my ‘day job’ and once I leave academia, I will be open to whatever kind of creative expression satisfies those needs. And I’ve just purchased a new piano, something I took up at a very beginner level when we relocated to Nebraska in 2000, and because of circumstances had to drop a few years ago. I’m on a quest to do justice to at least the easier Bach pieces in the keyboard repertoire, and I’m hoping too, that practice will have benefits of the cognitive kind.

What advice would you give to an aspiring textile artist?

Do what you love and love what you do, and do more of it, and more still.

Can you recommend three or four books for textile artists?

Well, that’s another can of worms. Too many to list. If I must, these:

- Makers: A History of American Studio Craft by Janet Koplos and Bruce Metcalf, and/or The Crafts in Britain in the 20th Century by Tanya Harrod. I’m always frustrated by how little textile “artists” – especially quilt folk – know of the wider world of 20th and 21st century studio craft. These books provide a fairly comprehensive overview of the history of the practices and the media associated with contemporary craft.

- On Designing by Anni Albers. Classic, and indispensable.

- Landscape and Memory by Simon Schama. This book was rich and hugely satisfying, and it made me wish for the opportunity to have Schama as a dinner companion. So far, that wish remains unfulfilled. We’re all connected to landscape at an elemental level, and this book is a sort of natural history of those connections.

- What Is Art For? by Ellen Dissanayake. Dissanayake has written a number of books on this general subject, “making special” as she prefers to call the practice of art making. They’re well researched and well argued, and although she suffered from some marginalization as a non-academic for a number of years, her ideas have since developed a following and achieved a wider level of acceptance. Very smart and perceptive at a deep level.

What other resources do you use? Blogs, websites, magazines etc.

I read a lot and broadly – history, natural histories of many kinds, poetry, biography, the rare novel (writers like Jonathan Franzen, Martin Amis, Donna Tartt, Alice Munro, Hilary Mantel and Richard Russo have been of particular interest). Newspapers, mainly the New York Times, now mainly online though I still buy the paper edition on Sundays. I don’t follow any blogs, and as for magazines, SURFACE and LAPHAM’S QUARTERLY are about it. I do have subscriptions to Surface Design Journal and American Craft.

What piece of equipment or tool could you not live without?

A pencil or pen, a writing/mark making tool.

Do you give talks or run workshops or classes? If so where can readers find information about these?

As a full time (i.e. 12 month) academic, I no longer have time to teach beyond the limits of the campus, though I do the occasional talk at conferences. I came into academia in part because teaching short-term workshops as I did for over twenty-five years had become frustrating. I wasn’t able to build long term relationships with students and watch them grow and expand their knowledge base, then build on that. This opportunity – to witness that growth – has been one of the more satisfying aspects of being in academia, and I’m proud of many of my former students and what they’re accomplished since going out into the career world.

How do you go about choosing where to show your work?

These days I’m primarily participating in invitational shows about which I can be fairly selective. Modern Arts Midtown in Omaha, Nebraska, represents my work in the wide central region of the US, and I show there fairly regularly. My current show at the IQSCM is my first solo show there. It runs through February 20, 2016.

For more information please visit:

- www.michaeljamesstudioquilts.com

- www.quiltstudy.org

- http://cehs.unl.edu/tmfd/

- http://www.modernartsmidtown.com/artists/Michael%20James

If you’ve enjoyed this interview with Michael James, why not leave a comment below?

I offer my sympathy and compassion in the loss of your beloved wife.

First of all thank you Joe and Sam for this wonderful interview with one of my favorite quilt artists.

Michael, so sorry to hear about your loss. Really admire your strength and the way you dealt with this sudden change in life.

It was really enlightening to read the interview and follow your path in the field of quilting. Your quilts have evolved so much through the years and it is fascinating to follow that path. Wish I could see an exhibit of your’s sometime in my lifetime. As I always feel seeing a whole body of someone’s work gives a whole different dimension. Thank you so much! ~ Boisali

You were my earliest influence in quiltmaking, I remember fondly a class I took with you in the 80s. Your continuous development as an artist is wondrous and inspirational. Such beautiful work, always.

A wonderful interview, from an early follower of your work. We share a similar sadness too ,you do return to work and live with the aid of that great healing medicine…time, and another journey commences

Thank you for this revealing and honest interview.

I saw the show at IQSC&M last month, as well as Judith’s show in the small gallery. Both are whole, rich statements that could only have been made after a lifetime of study and work.

Such a beautiful interview. Exquisite language. I saw both Michael and Judith’s work at Festival of Quilts, Birmingham some years ago and was entranced. So sad to hear of Judith’s death. My condolences.

In Columbus, Ohio I attended two classes under your very inspiring tutelage. My husband was very ill at that time, and I realize that I was not myself. It takes a long time to get over death of a loved one. I am so sorry to hear of your loss.

These latest quilts are the strongest that I have seen. Thank you for your continuing inspiration.

I’m so sorry for your loss. I hope you and your family find peace and comfort during This time.

Hey Daniel,

Loved your interview. I also feel sorry for the loss of a great human being from your life. Keep us inspiring.

Lots of best wishes for you.

I love your work and admire you as an artist. Your style is very special, love your colour combination. Very sorry about your loss. Please keep on creating for us. Best wishes

Hello from the Shetland Isles! I have chanced upon your interview in textileartist.org and absolutely love your work. Amazing colours, ideas and the various techniques used. Please continue on your journey with your beautiful ideas and pieces however large or small, it will help you greatly.

I love this article and you’ve shown some of Michael James’s best recent works.

Michael, your works are always inspiring for us. Please keep us inspiring with your creativity. Really sad for your loss.

Thanks for sharing valuable information with us. Your works are continually moving for us. It would be ideal if you keep us moving with your inventiveness.